And this feeling of the atomic self, equipped with nothing but a technique for self-consolation, means that you have no time for the sorrows of others.

Just yesterday, I published a list of the rote defences commonly mobilized by leaders of yoga and Buddhist organizations in which institutional abuse has come to light. I […]

An abuse crisis will often force a high-demand group to show outsiders what they inflict on insiders every day: loaded language, self-sealed reasoning, leader idealization, grandiose claims and image management techniques. If the group must admit abuse, it will show its unique harm calculus, and every emotional bargaining trick in the book.

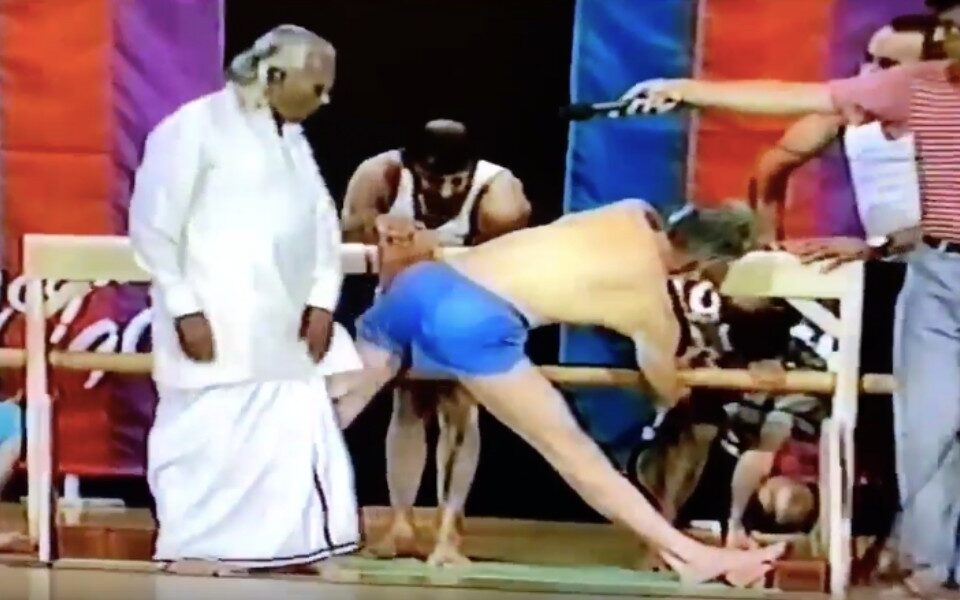

Ann Tapsell West posted two videos of Iyengar abusing students yesterday. If you don’t know West, her 2018 ethics complaint against Manouso Manos led to the […]