Negotiating the anxiety of influence (threads of yoga ephemera)

April 3, 2013

Ayurveda and the accusation of pseudoscience

May 21, 2013In both form and content, the work curated by Aghori Babarrazi presents a jagged paradox, true to his pseudonym, that defibrillates the limping heart of yoga philosophy. His crew consistently speaks for yoga-as-egoic-dissolution – through the most singular and eccentric voice of modern yoga literature. They repeatedly invoke the austerity of complete personal responsibility, while delighting in trash-talk from behind the scrim of anonymity. Aghori’s editorial paradox mirrors the dueling desires of yoga itself: to become, but to disappear. His masala of cruel empathy flavours the absurd task of making us naked and strange to ourselves, forcing us to wriggle, shift, and grow in the glare of our own contradictions. It’s a dirty, dirty job, but somebody – I mean nobody – I mean somebody who’s made himself a nobody pretending to be everybody – has to do it.

An article last week finally brought the full tension of Aghori’s project into sharp focus for me. In This is Probably What a Lot of Yoga Practitioners are Looking For, the Babarazzi critiques the “yoga-as-self-expression” trend within today’s yoga culture as the indulgence of the common desires, behavioural patterns and self-perceptions that he claims yoga is actually meant to erode. Babs proposes that doing what one is naturally drawn to do (singing, painting, design, fashion photography, ecstatic movement) and then laminating it with yoga-speak does a vain disservice to the tradition’s (allegedly successful) history of discipline and surrender to wordless authority, not to mention degrading the artform in question with a veneer of faux-transcendence. Babs also makes the subtler point that yoga-washing can become a value-added marketing meme that blesses any unchallenged consumerist activity with a self-satisfied glow.

The yoga-media critic must serve integrity by spotlighting the lines between evolution and self-entertainment, or self-consolation. But if we take the charitable view that “self-expressing” yogis really are nurturing their own integrity as much as self-erasing yogis are (and that further, that it’s arguably impossible to tell the two activities apart), Babs’ critique merely points to an honest problem as old as Indian philosophy itself: do we gain personal freedom and realize interdependence by dissolving or by refining our uniqueness? Babs suggests that this question has somehow been answered in yoga discourse. But it most definitely has not. In fact, the question expresses a key split within yoga philosophy. The ambivalent dance between the two views enriches the meaning of each, and it’s a great story in itself. I think it’s actually Aghori’s favorite dance as leader of Squad Babarazzi, regardless of the austere positions they pretend to take. (And when I say “pretend” – I mean to invoke respectful intrigue, à la Dérrida: “When I pretend to do the thing, I actually do it, so I must only be pretending to pretend.”)

Whether we must dissolve or refine our personality differences towards greater psycho-social-somatic harmony is the internalized version of the metaphysical question common to every system that considers the problems of language. Is “ultimate reality” describable, or not? The dissolution track (Patañjali and the Vedāntins) says “no”. But the refinement track (Nāthas, Babas, Aghõris) says: “let’s give it a try, and enjoy ourselves in the endless process”. In the Indian context, ultimate values that can be described and mimicked by aesthetic actions belong to a tradition of saguṇa (“with qualities”) liturgy. Ultimate values that must be formlessly pondered because we know they cannot be described belong to a tradition of nirguṇa (“without qualities”) liturgy. Using the context of Babs’ post, we could say that yogas that refine or accentuate personal uniqueness are playing in a saguṇa paradigm, insofar as the qualitative aspects of self-expression are emphasized, and felt to mirror the specific graces of the “divine” or “absolute”. Yogas that seek to dissolve differences are playing in a nirguṇa paradigm, insofar as qualitative uniqueness is felt to distort one’s reverie upon the quality-free absolute. Here, and in other posts in which he makes elliptical reference to the nameless beyond and elides the yoga of personality-erasure with the deconstruction of consumerism, Babs stakes out nirguṇa territory. This strikes a chord of common disgust: who among us is not at times sickened at the viral proliferation of memes, simulacra, yoga hoodies, and performed selves? Who is not at times exhausted by the tyranny of endless possibilities? Who does not, at times, despair at the fleeting dross of it all?

The nirguṇa impulse is at the heart of the cultural critic’s task, and surely its affect will intensify with the saguṇa overload of a spectacle society. Simply put, the nirguṇa mood is the reflex, audible as a constant refrain through Aghori’s curation, that says: “Nope. This isn’t it. It can’t be described.” In Nāgārjuna’s words: neti-neti. Nirguṇa head-bobbles with ironic and often bitter laughter, and calls out the foolishness of every platitude and hypocrisy, and every discourse or style that takes itself seriously. It’s a revolutionary impulse that in its highest expression carries the despair of all failed revolutions.

In Indian literature, nirguṇa language shows up in response to the claustrophobic hierarchy of Vedic culture: particularly the caste system. The earliest ascetic protests to the Vedic order say “Nope, this isn’t it” by stripping themselves of clothes, social signs, duties and privileges. They amputate themselves from Puruṣa – the macrocosmic man whose head was the priesthood and feet were the outcastes. Their refusal to participate in the social order harmonized with both their idealism and their democratization of the “absolute”. Ascetics have always, paradoxically, wanted to both leave and level society. They spurn both roles and riches.

But the ancient paradox – which Babs parades in all of its perversity – is that you can’t be a nirguṇa dude without sustaining a morbid fascination with saguṇa life. The energy of your renunciation depends upon the nausea of excess. To yearn for the quality-free involves constantly turning away from something. One can’t meaningfully withdraw to an empty or anonymous space from within empty or anonymous space. And so we witness Babs’ continuous obsession with the aesthetics and social politics of yoga culture. Whether it’s tone-deaf yoga-seva initiatives, or yoga capitalism, or the question of whether Sadie Nardini’s haircut is cyberpunk or steampunk, the world of self-expression is the self-erasure addict’s smack. It feels so good to take it, and it hurts so good to stop.

Often, the nirguṇa impulse seems more defensive or more angry than a simple “Nope, that’s not it”. It can feel triggered by a crisis of overwhelm: “Enough!” I’ve heard enough, I’ve seen enough, I’ve felt enough. Let me be free of the demands of thought, decision, self-consciousness, and being a self. Let me be free of the suffering of others struggling with the same task. I’m reminded of Stephen Porges’ Polyvagal Theory, which proposes that at a certain threshold of social-sensory excitation and complexity, the ventral vagus nerve (phylogenetically more evolved, running between the vital organs and the frontal cortex) begins to freeze, diverting autonomic energy to the dorsal vagus nerve (primal, unmyelinated, running between vitals and the limbic brain). The nirguṇa impulse sounds like it comes from ventral vagus overload – a drive to shut down, a drive towards pratyahara, a drive away from the moment by moment exhaustion of self-creation, re-creation, and re-creation. If we conceive of yoga as a strategy for toning ventral vagus nerve function, we might begin to see the nirguṇa impulse as a practice of last resort: the dissociative yoga you perform when you just can’t deal. You turn the wifi off, wrap a tensor bandage around your head, do some yoga nidrā, and feel self and other dissolve. You know you’ve recovered when the saguṇa begins to slip back in, right on the heals of the I-sense, like waking up from a deep sleep. You turn the wifi back on, and in it pours, this world of things: sweetly at first, and then pornographic. Nausea rises and the critique begins.

But the critique cannot help but to validate the view it is trying to derail: that appearances, styles, marketing memes really do matter. That how we perform our identities and adventures is of crucial importance, because identity is the medium of our being present to one another. The paradox of renunciation is that its poignancy is based upon the rising valuation of everything it renounces. The world denied is like an emotion suppressed: it grows until it bursts.

(Sometimes I wonder: is transcendence often an act? I rarely meet those who are more obsessed with the world than those who claim they desire to leave it.)

While the via negativa longs for invisibility, it can still cast a baroque shadow. Nirguṇa moods and aesthetics can be co-opted by the crowd, drift towards their own hegemony, and establish an unconscious saguṇa order. When the ascetic wanderers of the Iron Age begin to establish first ashram and then monastic life, the nirguṇa ethos becomes a powerful organizing principle. No one is special; everyone should wear a uniform; the teachings are bigger than the individual; the individual attains salvation through his or her group affiliation and adherence to the code – not through their personal gifts. Saṃgha (sharing the truth) is elevated over śramana (personal revelation). The first Buddhist monks were instructed to gather rags from charnel grounds and sew them together, and then dye them uniformly into robes. This was at once an avowal of interdependence (through scavenging), a sign of renunciation and poverty, and a sacrifice of personal affect. The robes conveyed an anonymity that reflected the post-egoic yearnings of the religion.

At least for a while, and only on a small scale. To reject the clothes of your station and wear the style-less rags of the common dead is a radical, nirguṇa act. But just as the band that can never be cool again after other hipsters discover it, the more dudes who join up, the less quality-less the choice. The robe, conceived to erase all uniforms, slowly becomes a uniform itself, an expression of personal allegiance and choice. A new form of self-expression, in fact. Over time, styles of how to assemble the robes emerge. The number of patches becomes an indicator of years of seniority or a mnemonic device for now-ossifying articles of faith. As enlistments increase, new efficiencies in robe-making must emerge. Soon, each monastery has a tailor, and robe-fashion begins to take on adornments of position and status. As qualities creep in, the philosophical emphasis upon no-qualities rings hollow, priming the next generation of those who will say “Nope. This isn’t it”, or, more angrily: “Enough.”

And so the oscillation tilts. Nirguṇa needs saguṇa to enjoy the surprise of its emptiness. Saguṇa needs nirguṇa to give the senses a break. Nirguṇa becomes saguṇa over time, and must recover itself through renewed revolt. Babs needs Sadie’s haircut to reveal the absurdity – but also the ecstasy – of style. And it could be that Sadie needs Babs to remember that for all of the roles she is playing, she is still, like all of us, nobody.

There’s an additional complication that I’m sure Aghori’s inner anarchist is aware of: that nirguṇa mood and diction can have a reactionary affect. As Joel Kramer and Diana Alstad point out abundantly in The Guru Papers, the language of nirguṇa metaphysics – as we hear it ring through both ancient and modern non-dualism– can be used by an authoritarian culture (or even a lone-wolf blogger) to chill the dialogue of learning. It is just too easy for sentiments like “God cannot be understood”, “if you haven’t had the experience, stop talking”, “the mind doesn’t have the answer”, “your reasoning can’t help you”, “Practice, practice, and all is coming”, or even “yoga has nothing to do with self-expression”, to be used to suppress the very kind of questioning that is Babs’ food as critics. Such claims of ultimacy are too easily interpreted according to their presumed factual rather than performative value. But Aghori’s curation brings primarily performative value to the table. He farts on the cocktail wieners and tinkles in the punch bowl. He inverts and subverts, but breaks no news. He provides rhetorical disruption, which is its own form of wisdom that plays with the ways in which we make meaning, but cannot itself establish facts. And how in the end could we glean facticity from a writer who is himself fictitious?

Which brings me to the nirguṇa/saguṇa paradox of Aghori’s anonymity, and that of his cohorts. Writing under a pen-name is at once an act of self-erasure, and self-and-other construction. Because he is a blank, a cipher, he can take on any excess of personality he pleases. Aghori is no-one, but potentially everyone, a bald monk with a closet of zoot suits, skinny jeans, Banksy hoodies and rainbow wigs. He’s free to pluralize himself with other anonymous collaborators, which further obscure his individuality while showcasing his internal archetypes. Like some fabulous yidam, his content might cry out for a quieter union, but his form splashes pluralism loud and proud.

Some months ago I messaged Aghori to say I wanted to mail him a copy of my book for entertainment, and maybe to review if he felt so moved. He wrote back and said he had no mailing address. I asked if he had a work address or the address of a friend who might receive the book for him. No, and nope – maybe later. I was briefly concerned he might be homeless, and had an awkward fantasy about sending him money. But then came daily Babarazzi posts at 5am EST for three weeks straight, tightly-written, well-designed, and smartly-managed as the comments flowed in. So I was satisfied he had a roof, high-speed, and was eating protein. But I felt something else while reading the posts compulsively in the pre-dawn: here was the part of me who is anonymous and anarchic. Here was the part of me that after fifteen years of meditation still closes his eyes to see absurdities. Here was the part of me who could be anyone with any thought at all, who could awaken into the world every day with my dream-language unbroken.

In Indian horary astrology, the two-odd hours before dawn is called brahma muhurta: the “hour of expansion” (according to my post-religious translation). It is said to be the most auspicious and efficient time for practice. Perhaps Aghori edits at night, and simply cues wordpress to publish before dawn, so that the post shows up at the top of his readers’ inboxes. But he must know that it is the time of sādhana, and that for his readers who are less-than-completely disciplined with their devices, his absurdist sermons will interrupt and then inform their practice. I’m willing to bet that for Aghori, critique is itself a sādhana, in which he erases and rebuilds both self and other, and one he wishes to interject into the strange, anonymous saṃgha we belong to, by chance or by choice.

But as the morning gathers, the saguṇa thickens, along with its discontents. One recent mid-morning Aghori posted a lonely request on his timeline: “Friends: give me something to write about”. Part of me felt like he was asking what we ask of each other, and of yoga, constantly: “Who should I be today?”

I answer: write about the anxiety of this threshold between being something and being nothing. Write about the pain of having to be so smart, every single day, and smarter still, as our complexity rises. Write about how the world rushes into the heart until it is too full, and we want to fall blank and silent. Write about the terrible guilt of the critic. Write about how not self-expressing is simply the expression of a quieter self. Write about how it is just as harrowing to share something through the mirage of selfhood as it is to try to disappear. Write about how self-expression is itself erasure, being a palimpsest upon previous selves. Write what you would write if you could never be anonymous again. Write about the impossible ideal of your pseudonym, Aghori, which means “without fear”.

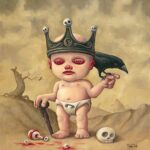

image from www.joeyl.com.