WAWADIA /// My Left Hand: I Am That (draft excerpt)

November 11, 2014

WAWADIA Update #19: Thomas Myers Misdefines Pain. But Why?

November 14, 2014Please consider supporting the fundraising campaign to support the book that is emerging from this research.

_____

I spent October 13th in Manhattan, doing two interviews for the #WAWADIA project. I’ll tell the story of that day here, and then publish excerpts from some of the source interviews soon.

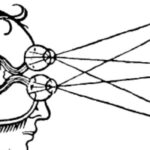

My first meeting was in the morning with Lindsey Clennell, a 40-year practitioner of yoga from Britain, and an award-winning film maker to boot. I wanted to ask him about the documentary that he’s making with his son Jake, called “Sadhaka”. The film is an homage to the legacy of his teacher, B.K.S. Iyengar. I was especially interested in asking about the visual metaphor that opens the gorgeous trailer they’ve released to help promote their project. (The trailer is linked below.) In the metaphor, Lindsey and Jake compare the work of Mr. Iyengar on the human body to the work of a local stonecutter carving an icon of Hanuman.

The first words of the trailer belong to the grizzled artist:

One cannot begin work on a sculpture without courage. The nature of a stone is that it is strong. To transform it into a sculpture, and see God within it, requires immense strength. If one gives up or is daunted by the strength of the stone or injuries, the sculpture will never come to life.

That evening, I ate take-out noodles off of Leslie Kaminoff’s treatment table in his office at The Breathing Project. Joining us were Amy Matthews and and their long-term student and assistant Sarah Barnaby.

This wasn’t my first visit. I’d interviewed Leslie about six months before about the possible role of better anatomical education in injury prevention. This time, I was eager to ask Amy about the work she does to integrate the latest research in infant developmental movement into asana.

An IDME-trained practitioner, Amy runs a Friday morning class for caregivers and their infants from newborn to walking. “The focus of the class,” as she wrote to me by email, “is a little bit of facilitating baby movement, and a lot of educating the caregivers about how to support the babies in their learning and being. Many adults — mostly asana students — can observe the class, and discuss afterwards how the principles might apply to their own movements.”

Amy’s work reminds me of this passage in the Jnaneshvar-Gita:

That is called [yogic] action of the body in which reason takes no part and which does not originate as an idea springing in the mind. To speak simply, yogis perform actions [called asanas, kriyas, bandhas, and mudras] with their bodies, like the [innocent, natural, sahaja] movements of children. (1210/1987; thanks to Stuart Sovatsky for the reference)

So we have the stonecutter, and the baby-whisperer. The values of the entire last century of modern postural yoga would seem to oscillate between these two icons. On one end of the mālā-string, a harsh discipline seeks to reconstruct the person into a worthy vehicle of devotion. On the other end, we’re encouraged to release every discipline and habit that has obscured the original ease and pleasure of movement. Modern yogis slide back and forth on that string, like beads, in constant dialogue between the desire for a new self and a primal memory.

On the train back to New Jersey that night, my brain swirled with the contrast of the two encounters. At 10 am, Lindsey had served me English Breakfast tea (probably from Harrods, it was that good) with cream and honey in his tidy Greenwich flat as he regaled me with his stories of asana’s recent history. At dusk, Leslie tipped what looked like expensive tequila into my Thai pomegranate lemonade and twirled around in his office chair, grinning broadly as we listened to Amy paint her picture of asana’s near future.

As I stepped out into the night fog of Morristown, I realized: this day is like the book itself. It has to cover at least a century of asana theory, for sure. But more importantly, it has to cover a century of paradigmatic shifts in just about everything having to do with how we feel asana, from the ways in which we feel effective pedagogy on the studio floor, to how we feel the very origin and purpose of the body. It has to move between times and cultures, interrogating traditionalists and innovators, seeking clashes and harmonies. It has to be careful not to confuse tradition with reality, or novelty with progress. It has to be careful not to throw the baby in with the stonecutter – to somehow keep them separate, and separately valued for what each offers each yogi in their time.

____

The trailer for Lindsay and Jake Clennell’s upcoming documentary “Sadhaka” seduces with its rich visuals, elegant BBC pacing, and contemplative edits. The first time I watched it I was really happy that an intelligent story had found an expert teller, and some funding. But as I drifted off to sleep that night, I replayed the visuals in my mind, and somehow they felt off.

Here’s the generously-long excerpt, which the Clennells have posted to help attract investors…

Sadhaka: the yoga of BKS Iyengar trailer from Lindsey Clennell on Vimeo.

…and here are the several thorns that stuck in my side, from the first six minutes:

Stones and expectations. A human body is not a stone. It’s not covering up divinity, at least as far as I’m concerned. You can chip away at it all you like, but every “improvement” will leave a scar. Many therapists feel that the body may contain emotions or memories that long for release. But the release rarely happens through force, and it never happens according to the prior ideals of the therapist. The stonecutter knows exactly what he’s going to carve before he starts. The competent therapist has no plan beyond rich dialogue.

Boundaries and objectification. The student in shoulderstand has apparently given consent, but to this extent of total surrender? She cannot get into or come out of the posture on her own. The props are applied to her as though she were a fruit tree being shaped. The camera shows her face only once, obscured by her shirt. The focus is on her legs, parts subject to correction, isolated from the rest of her person. Legs that look sturdy and strong to me. At one point the camera shows her legs surrounded by three men, all slightly frowning, wondering how their handiwork might be improved.

Most of all I wonder: who is this woman, and why is nobody asking what she’s feeling? And: how much of modern postural yoga so far has consisted of older men telling younger women how to position their bodies, and what to feel?

Micromanagement. Iyengar corrects her and corrects her and corrects her. Where does it end? Toward what ideal? When the stonecutter sands the final ridge of limestone from Hanuman’s cheek, the icon is done. But what of the body? What has improved? Did this woman present him with some kinesiological issue that she wants to iron out? Does he see something she doesn’t notice? We don’t know. I for one get the impression that the corrections are being made not to correct anything of substance, but to assert a particular power. To place the subject in the mode of continually answering to a demand. A divine demand, no less. The stonecutter says:

The soul directs us as we sit there. It says “This is the way it should be done. This is the way.” This is what we call the life force or higher soul. As we work, it tells us what to do at each moment. “How should this be done? What should it be on this side and that? What’s the difference between this implement and that? This eye and the other?” All this is controlled by ego, soul, and the supreme self. They keep making subtle adjustments every moment.

Iyengar, the film suggests, is the very soul of the practitioner, sculpting her towards her perfect form. I wanted to ask Lindsey if that’s really what he intended.

I swigged my tea and steeled myself to present my raw analysis to him. I didn’t pull any punches. Lindsey smiled broadly and said “Thank you for saying all that, and thank you for coming and seeing me, because it’s quite interesting. It presents us with an interesting decision.”

So right off, I knew I was speaking to a yogi. What I mean is that a yogi is someone who can happily entertain a critical view of their labour of love (even when that love has a budget that will grow to at least a half-million dollars), and, without a shred of defensiveness, offer a passionate response. We talked for two hours, and he addressed all of my thoughts with a well-considered view. Here’s an excerpt from our dialogue that cuts to the heart of things:

____

Lindsey Clennell: Your question is, ‘Is the affliction defined as being in the body? Is he correcting the body?’

MR: I have many questions, but that’s a good place to start.

LC: No. The affliction is really mental. It’s Patanjali yoga. But, as Iyengar says, ‘You people talk to me about meditation, you want me to teach you about meditation, and you can’t keep your legs straight for three seconds. Why do you want to talk about meditation?’ Right? It’s because they can’t manage their attention on something. To manage your attention on some – as Buddhists might say – emerging negative characteristic – it must be sensed in order to manage it. It’s too late when it’s overwhelmed you.

So how do you learn that skill? You can’t say, ‘That’s what you’re going to do now, okay. Right, I’ve told you now, now go away and do it.’ What you need to do is train somebody, to manage their attention, and to manage it from objects that are gross to objects which are subtle, and then move on to the mind. So if I can straighten my elbow – look at that [gesturing a fluid arm extension] – or my wrist [extending a graceful wrist], what’s the difference? There’s a difference between those two actions.

And if you look at a class, how somebody straightens their arm, or straightens their legs, or raises their chest, or does this, or does that, progressively you’re teaching them, through different levels, to be progressively more subtle in the observation of their body! Simultaneously, they become more aware of their actions on a mental level. That’s the trick, that’s the trick.

MR: So you believe the mechanism is one of focusing awareness; it’s not accomplishing a form, or –

LC: There you go.

MR: However, there is a bias towards the straight.

LC: Strength? Do you mean strength?

MR: No, straight. Towards the straight line.

LC: Oh, straight. You mean like the alignment.

MR: Alignment, yes, but also a kind of architectural straightness. We see it figured in the logo of the institute itself, in which Iyengar’s body is in Natarajasana against the Twelve-Windowed Pyramid. It has this perfect geometry, which looks kind of like a secular yantra, right? And what I was fascinated by, is that here is a Kapha woman. Here is an earth-and-water, full-figured person, who is round and curvy.

LC: Sure, sure.

MR: – and she is being straightened. And because I can’t tell what needs to be straightened, I’m wondering about the influence of the straightness bias. Now, if it’s simply a way of directing attention, can you straighten something that normally wants to curve but may not be dysfunctional – then that’s fine. But it seems to me that there’s a geometry of form that is prized within the system in general, that speaks to a way of taming what would be seen as, you know, the untoward curves of nature.

LC: “Aberrant” nature.

MR: Yes, exactly.

LC: Right, right. I think if you look at Light on Yoga, and you look at the pictures – first of all, if you’re uneducated in asana, you ask ‘what the hell is this guy doing.’ If you’re, sort of, more educated in asana, you would look at not the straightness of them, but the organic nature of them. They’re very organic-looking. They are symmetrical. The thing – if you look at him sitting, and I facebooked a picture, I put it out – I said, It’s an oldie, but look at the symmetry – just look at the symmetry. So the idea of comparing the left and the right, bringing symmetry to the body, really undoing things that have gone wrong in the body, is really I think what it’s more about. What you’re picking up on, is something which, you know, as I said earlier, maybe we should have the sticks in or not, but really what he’s doing with the subject is probably teaching her that she has got legs.

MR: That she just has legs?

LC: Yes. So many times, when you see him propping somebody, he’s like giving some reinforcement, that now you’ve got a knee. You’ve got a knee there. Whereas previously you didn’t know you’d got a knee.

MR: You were disembodied.

LC: You didn’t know you’d got hips. You didn’t know you’d got shoulder blades. You didn’t know you’d got eyelids. You didn’t know you had all this stuff.

____

As Lindsey spoke, I got something, finally. So many years after drifting away from a lineage that I’d found increasingly rigid, led by a man who sounded more and more like a dictator than a therapist, I remembered why I’d been attracted to him and his senior students in the first place. For one thing, their certainty about things (or was it merely their wish to transmit confidence?) pushed some very old buttons within me. Before them, I regressed to the safe deference I’d affected as a child towards religious authority.

But on the other hand, for all of the gesturing towards Patanjali and Vedanta, these teachers were consummate materialists. They may have speculated on the effects of kidney breathing, but they didn’t waste their time with metaphysical dreams. Their uncompromising voices called me sharply into a critical appreciation of my physical condition more intimate than I’d ever known.

Lindsey was right. Ramanand Patel taught femoral grounding and shoulder stability and spacious breathing and mula bandha through a thousand different and irritating instructions. I’ve forgotten all of the instructions and couldn’t care less about those skills any more. But I’ve never forgotten that I actually have a body. I’m more confident in my embodiment now, and I think I have this method, as well as becoming a parent, to thank.

Perhaps the famous prickliness of some members of the Iyengar system comes from more than the master’s mood. Perhaps it communicates a more general, humanistic outrage: How can we dare to be here, walking around, and not develop the feelings of this flesh, this most fundamental sign of life and grace? It is an anger directed at a disembodied global culture that thinks it can move beyond the virtues of physical presence and labour and the awareness that rises from it, and still think we know something about life. It is an anger that soured for me quickly. But it was helpful for a while.

That vinegar reminds of the time my therapist asked me: “So when are you going to stop bullshitting?” He only needed to say it once. I stayed with him until I needed a different type of conversation.

Here’s one very important thing I learned about that film from Lindsey. The woman in it? Her name is Abhijata Iyengar. She’s his granddaughter. So that puts a different spin on the whole scene, though I’m not sure what it is, because all families are mysteries.

_____

Between my meetings I had time to visit the 9/11 memorial. Two perfectly square depressions plunge into the earth: towers in reverse. Water cascades down the granite walls into a rippling pool which is itself punched downward with another perfect square at its centre, into which the water disappears like time. It’s such a perfectly executed work of geometry, nondenominational dignity, austere idealism, and endless crafted movement, I wondered whether the lead architects were students of Iyengar yoga.

_____

Leslie, Amy, Sarah and I talked about a hundred things that evening. I’ll limit my reporting for now to Amy’s take on the metaphor of the asana teacher as stonecutter.

They hadn’t seen the film, so I described it to them. I got to the description of Iyengar forcing the ropes down on Abhijata’s calfs and then shoving rods into the ropes to splint her knees (rods that look an awful lot like the muchan cudgels of Kalaripattayu). Amy started shaking her head. She put down her chopsticks and took a deep breath:

____

Amy Matthews: So what you’re describing goes against everything we now know to be good for movement education, if we’re actually going to take our own developmental reality seriously. If we look at how babies learn to move on their own, autonomically, intuitively – producing the entire toolbox of skills that we end up applying to every other task in our lives – we know that they do best when we let them find their own sources of support. They are in a process of learning how to get into positions that they want to get into – pleasurable positions, functional positions, asanas, really – and if we intervene in that learning stage, we set them up for a whole range of tensions that may not be useful or necessary.

MR: Okay, so if you constrict that process, manipulate it –

AM: Yeah. So the idea in the Body-Mind Centering approach to developmental movement is that learning to get into and out of a position is as important as being in the position. With an infant at four or five months, you might be able to train them to sit, by putting them in a position and then taking your hands away. So we can train them to do something, but it doesn’t mean they have learned how to do it. So sitting and standing, before they know how to do it, has repercussions in terms of the relationship to gravity, their sense of themselves, their sense of agency about engaging with rising and falling, and getting into and out of – so there’s this bracing that arises, because they don’t know how to fall. [Makes a sudden spine-stiffening gestures, and I remember very clearly what it felt like to stiffen into the demands of a pose, especially when guided by props.]

MR: Which might be the beginning of an anxious relationship with the notion of supporting oneself.

AM: And which would interfere with a sense of agency, I would say, and distort the sense of one’s own weight – about a sense of my own weight and its relationship to gravity. My sense of ability to get into and out of the position and then my – yes – self-reliance, and then my sense that ‘I can do something about it.’

MR: So interventions in movement can actually disrupt something crucial.

AM: Yes. The process of negotiating my weight, in relationship to gravity, and then learning to move out of gravity, but then also learning how to fall. So part of the idea is also that small falls are very important. We often protect an infant from falling, starting with the rolling from side to back, or side to front. Of course we don’t want them to crash their head into the floor. But when an infant’s head bonks on the floor a little bit, they learn something. We’re not talking about neglect. But we learn something that we fall. Pain isn’t necessary, but there’s a point where it’s not pain; where it’s information.

We often protect an infant from falling more than is necessary, and get in the way of the learning that happens with small falls like rolling from side to back, or side to front. We learn something when we fall.

Sarah Barnaby We learn in each of the places between being from where we came to, up to where we are, rather than just –

MR: – Like — all of the asanas within the vinyasa.

AM: Yes. All of the places in between are really important.

MR: So when we have this display of a hyper-propped individual, who’s almost in splints – what I see is that all of the resilience that would come from being odd, from being roll-y, from bouncing, really – all of that softness suddenly must be straight. Has to be straightened out. To me, there’s a metaphysics to it, right? I just kept looking at that and thinking about that old – maybe it’s a Chinese – proverb? ‘The risen nail will be pounded down’ – something like that. That everything should be a smooth surface.

AM: I think there’s some assumptions about what is functional, and what is efficient. A mechanical model doesn’t describe the way the body works. In our body, force does not have to travel in a straight line. A clear pathway is not the same thing as a straight line. We’re all curved surfaces, and we can be curved on the outside and have a clear pathway on the inside.

Iyengar seems to be expressing — but it’s not only his idea of course – that there’s some idealization of the human form that says that the more mechanical we are, the more efficient we are. And it turns out, as we gain more and more understanding of the biomechanic-physics-chemistry of the body, that the mechanics, physics and chemistry of the body are not like a building. We don’t work like buildings.

____

As I went to sleep that night I thought of parents and children, teachers and students. Discipline and permission. About Abhijata being in an asana that she couldn’t get herself out of – not only a bound shoulderstand, but the family position that will so strongly influence the rest of her life.

I thought of all of the moments of sternness in my education, every time an older man met my distraction or apathy with a jolt: wake up, look alive, straighten up, time is short. I thought of all the times this was useful. About how it showed me I had legs. I thought about all the times it went a little too far, invading me with the teacher’s own anxious projection, or the militarism of an entire culture.

I thought about how eternally hard it is to find the line between these competing teacherly desires: to lead and to allow.

I thought about Lindsey, almost seventy now, spry and hopeful and inspiring. Near the end of our interview, he spoke eloquently about how all that Iyengar really wanted to teach was a kind of confidence. I thought of the confidence that comes from being supported, in contrast with the confidence that comes from learning to support oneself.

I thought of Lindsey editing this last cinematic love letter to his teacher. I wondered about the shadows and ambiguities left on his cutting-room floor, and what will come of sifting through them.

______

Thank you to Jason Hirsch for excellent and timely transcription.

______