“Vedic” Astrology: A Strange and Lovely Art from Time Gone By, Rife with Tender Bullshit Today

March 17, 2014

20 Suggestions for Doing Yoga Philosophy Today

March 29, 2014I imagine the redeye back from LA is always a ripe time to reflect upon the mirage of identity, and the mind.

Particularly: how illusory things become true, and how things that once were true erode. How during a life one can move from West-coast credulity to East-coast disenchantment and on to Wherever-You-Wake-Up-This-Morning re-enchantment.

On this particular run, I had Deva Premal’s track of Śaṅkara’s Atma Śatakam (“Chidananda Rupa” — posted at the end) on continuous loop as I sat squeezed and stiff but happy, half dozing and half meditating in my rickety coach seat. The sign said “Bottom Cushion Can Be Used as a Flotation Device.” Indeed.

It’s a poem (reproduced with commentary below) that in its traditional reading stands for everything I reject in extractive/abstractive philosophy. It lays out the classic non-dual position: the multiplicity of experience is illusory, because there is but one unified purity of consciousness. Multiplicity consists of ephemeral waves upon the ocean. Weather passing through the sky proves the difference between what changes and is therefore unreal, and what is eternal. And so on.

In its meticulously rich six stanzas, the poem runs through every phenomenological fact and social construction of the human condition, disidentifying with each. The poet Śaṅkara (788-820) is emphatically not his emotions, intelligence, flesh, language, heritage, moral position, or mortality. He rejects everything that both interoceptively marks him as human and that discloses him as a social being. In denying his embodiment and sociality, he denies everyone’s. If his true nature cannot be seen — and because of this, his viewer must be seeing a mirage — his viewer’s sanity, and even ontology, is silenced. The unacknowledged and unintentional violence of Śaṅkara, sitting in serene perfection at the head of a parade of haloed inheritors, is that he cannot deny the signs and particularities of the self without doing the same to the other, and therefore to all others. What right does he have to anoint himself at the centre of a universe of sameness? Is everyone longing for their differences and different positions to be erased?

It’s not a stretch to speak of the violence of non-dualism or any “Oneness” movement when we consider its appropriative mechanism. There might be better descriptions of it, but the one that struck me first and stays with me is that from Joel Kramer and Diana Alstad in The Guru Papers (North Atlantic, 1993, 348-354). They write:

Oneness, the pinnacle of religious abstraction, is the aspect of Eastern thought the West is currently the most enamored of. The early Vedism of the Aryan invaders that superimposed itself on indigenous forms was a combination of polytheism, ancestor worship, and ritual sacrifice similar to Greek and other Indo-European religions. Later… the more sophisticated Upanishads put forth the conception of Oneness, the non-duality of being (advaitism). In Hinduism, Vedanta is the modern expression of this. This raised the level of abstraction in Hinduism to where Brahman, The One, actually encompasses everything. As with all abstractions, here all differences are ignored and an all-permeating sameness given to ultimate reality. However, differences still must be accounted for, even if they are trivialized by calling them illusion (maya). With the abstract concept of maya, which includes all differences under the same umbrella (the multiplicity of existence), diversity is both accounted for and either denied or made lower.

Kramer and Alstad go on to describe how Advaitism, as the highest of religious abstractions, functions to colonize all other abstractions: Mahavira, Buddha and Christ alike become avatars for a truth they themselves can’t fully express. In the contemporary yoga world, Advaitism extends its reach via an “it’s-all-good” call to sameness that utterly fails to challenge the hegemony of neo-liberalism, which itself offers a cynical shadow-message of the same import: everyone and everything is equal in the mysterious glow of the totalizing Brahman market. Of course, this is all complicated by the fact that Śaṅkara also saw himself and was seen as a social reformer, who in his rejection of social construction was making yet another attack upon the caste structures that have proven resilient to the present day.

Śaṅkara’s scant biography might illuminate the poem, a bit. Blessed by legend with perfect auditory memory, he is said to have memorized the Vedas and vedangas on a first hearing at the age of six. He is said to have spontaneously composed the Atma Śatakam at the age of eight, in response to his future guru Govindapada’s question “Who are you?” There is no way of verifying this, of course. Occam’s Razor would suggest that the story is rich in hagiographic embellishment, and that the text itself, like all ancient texts, has been palimpsested countless times.

To repeat: by tradition, this summary statement of Advaita Vedanta is claimed to have been written by a prodigy at the age of eight years old. Taking this part of the story to be true for a moment, how different is the series of rejections that Śaṅkara utters from those made by any simmering pre-teen? Who isn’t stomping their foot at the door to adulthood, rejecting the overdeterminations of elders? It usually happens more in the 12-14 year-old range, but it’s pretty clear that the boy was precocious, regardless of when he spoke whatever went on to become the poem we have now. It’s would be a precocious poem for a scholar of thirty-two, at which ripe old age Śaṅkara died, possibly, in armed conflict with the Buddhists he supposedly reviled. (Other sources say that he was a crypto-Buddhist all along. That the alternate name for the Atma Śatakam is Nirvana Śatakam sheds light on this ambiguity.)

The rejections so necessary to developmental psychic individuation (Śaṅkara says “I have no father or mother”) are often grounded with re-assertions of identity from a place of wished-for autonomy. In the poem, Śaṅkara’s reassertion shines through the refrain “I am the unified form of conscious life and bliss, I am Śiva.” Systematically, he rejects every name and form to replace them all with another. The pattern for each verse consists of nine rejections and one assertion. The first verse looks like this:

- rejection of identification with the emotional-sensory mind

- rejection of identification with the intellect

- rejection of identification with the ego principle

- rejection of identification with mundane consciousness

- rejection of identification with the senses

- rejection of being composed of space

- rejection of being composed of earth

- rejection of being composed of fire

- rejection of being composed of wind

- assertion of identity as pristine consciousness

That Śaṅkara uses nine rejections in each verse constitutes a numerological dismissal of the phenomenal world. Nine is the number of experiential wholeness: there are nine planets, nine emotions, nine squares in the nava chakra that forms the planetary grid and builds up the Śri Yantra. There is distinct method to his rhythm. With every nine-fold list, Śaṅkara erases the world. With the tenth item, the assertion, the poet converts himself into the object he wishes to be, the object of his groundless devotion.

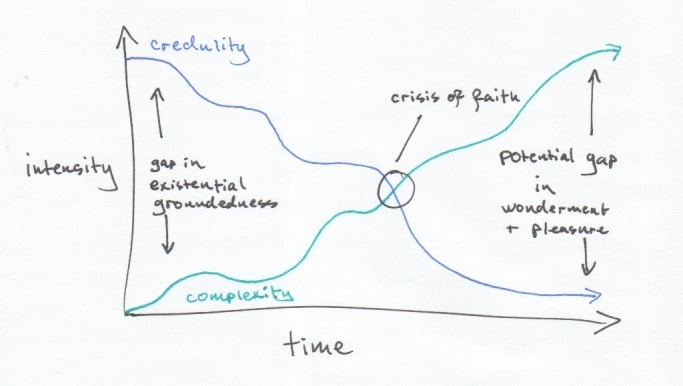

Śaṅkara’s tender age and what I at least hear as the naïveté of his poem got me thinking about the difference between the adolescent rhythm of rejection/assertion, versus what comes with a little more life experience. And what comes, transhistorically, with the refinement of the sciences. With age, consideration, and the slow drift from credulity to complexity, it seems we generally move from rejection/assertion to rejection/possibility. This is certainly the pattern with science, which systematically rejects impossible answers to narrow in on answer(s) that is/are only ever possible or provisional. In matters of the heart, meanwhile, each new identity shift seems to drain one’s capacity for reasserting a self. By forty, one might relax into the realization that one will never know who or what one is, and that perhaps it’s not an important question.

British psychoanalyst Adam Phillips says: “Answers do not answer questions. Questions answer questions.” I say to Adi Śaṅkara, so young, so sure of his halo: Śiva cannot be your final answer. Or if it is, it is because you dreamt of it in your youth, and then you died too young.

In this light, on this sunrise-bound plane, humming at 30K feet, with hot steamed milk with nutmeg and honey in my thermos, and Deva Premal’s relaxed lilt in my ear-buds, I start hearing the poem differently. I move into remix mode.

What if we take “Śiva” to be Śaṅkara’s provisional answer — as it must be, coming at the age of eight? The Advaita conceit is that the deity’s name is already a pseudonym. “Śiva” is one of many possible transcendental placeholders for nirguna brahman — the “absolute without qualities”. In root form it means simply “auspicious”. Advaita offers an answer without a name. But going further: must we settle for even the feeling of an answer? Will we always need that particular consolation of theology? Every answer seems to conceal an absence. Every answer pretends that things are not still moving. And who would rest with the assertions of an eight year-old?

With this in mind, I’ll gloss the poem, offering possibilities in the place of assertions. The transliteration, Sanskrit, and translation are all grabbed from Wikipedia.

Atma/Nirvana Śatakam

- manobuddhyahaṃkāra chittāni nāhaṃ

- na cha śrotrajihve na cha ghrāṇanetre

- na cha vioma bhūmir na tejo na vāyuḥ

- chidānandarūpaḥ śhivo’ham śhivo’ham

(मनोबुद्धयहंकार चित्तानि नाहं, न च श्रोत्रजिव्हे न च घ्राणनेत्रे । न च व्योम भूमिर्न तेजो न वायुः, चिदानन्दरूपः शिवोऽहम् शिवोऽहम् ।। 1 ।। )

I am not the emotional-sensory mind, nor intellect, nor ego, nor the reflections of inner self (chitta). I am not the five senses. I am beyond that. I am not the ether, nor the earth, nor the fire, nor the wind (the five elements). I am indeed, That eternal knowing and bliss, the auspicious (Shivam), bliss and pure consciousness.

____

Gloss: In current neuroscience, consensus is gathering around the proposition that selfhood is illusory. We confabulate selfhood from a series of cognitive habits. The self can disappear if these habits are broken. Self-awareness seems ephemeral both in terms of its inconstant appearance (where is the self when you’re not thinking of the self?) and because it cannot be found within or limited to the traditional divisions of mentation that Śaṅkara provides: emotional-sensory mind, intellect, ego structure, etc. Perhaps “Śiva” is not an asserted selfhood, but a description of the fruitless, haunting, poignant chase after the self.

____

- na ca praṇasajño na vai paṃcavāyuḥ

- na vā saptadhātur na vā paṃcakośaḥ

- na vākpāṇipādaṃ na copasthapāyu

- cidānandarūpaḥ śivo’ham śivo’ham

(न च प्राणसंज्ञो न वै पंचवायुः, न वा सप्तधातुः न वा पञ्चकोशः । न वाक्पाणिपादं न चोपस्थपायु, चिदानन्दरूपः शिवोऽहम् शिवोऽहम् ।। 2 ।। )

Neither can I be termed as energy (prana), nor five types of breath (vayus), nor the seven material essences, nor the five coverings (pancha-kosha). Neither am I the five instruments of elimination, procreation, motion, grasping, or speaking. I am indeed, That eternal knowing and bliss, the auspicious (Shivam), bliss and pure consciousness.

____

Gloss: What is this flesh? How do I live in it, or though it? How am I it? How is this flesh myself? How does it betray “me” when “I” am sick? Śaṅkara didn’t live for long enough to justify negating the body, which takes on a non-negotioable presence and thickness with age. We have no evidence beyond conscious reporting that conscious faculties reside anywhere outside of the flesh. And yet the dialogue continues, as though we are internally split: “What is that feeling?” “Why can’t I move in the way I want to or used to?” Self-awareness, product of the tissues, is the phenomenological basis for what allows Śaṅkara to believe “he” is separable from the tissues. The internal conversation alone can provide a lifetime of wonder and consideration. Perhaps “Śiva” is the pulse of this conversation.

____

- na me dveşarāgau na me lobhamohau

- mado naiva me naiva mātsaryabhāvaḥ

- na dharmo na cārtho na kāmo na mokşaḥ

- cidānandarūpaḥ śivo’ham śivo’ham

(न मे द्वेषरागौ न मे लोभमोहौ, मदो नैव मे नैव मात्सर्यभावः । न धर्मो न चार्थो न कामो न मोक्षः, चिदानन्दरूपः शिवोऽहम् शिवोऽहम् ।। 3 ।। )

I have no hatred or dislike, nor affiliation or liking, nor greed, nor delusion, nor pride or haughtiness, nor feelings of envy or jealousy. I have no duty (dharma), nor any money, nor any desire (kama), nor even liberation (moksha). I am indeed, That eternal knowing and bliss, the auspicious (Shivam), bliss and pure consciousness.

____

Gloss: For those who can manage it, and for however long they can manage it (maybe only in spurts), this is one possible response to capitalist hegemony: I will not let you profit upon my unconscious drives. I will not participate. Here, Śiva is the voice of a civil disobedience so complete it excludes itself from the rules of culture to dream something new.

____

- na puṇyaṃ na pāpaṃ na saukhyaṃ na dukhyaṃ

- na mantro na tīrthaṃ na vedā na yajña

- ahaṃ bhojanaṃ naiva bhojyaṃ na bhoktā

- cidānandarūpaḥ śivo’ham śivo’ham

(न पुण्यं न पापं न सौख्यं न दुःखं, न मन्त्रो न तीर्थो न वेदा न यज्ञ । अहं भोजनं नैव भोज्यं न भोक्ता, चिदानन्दरूपः शिवोऽहम् शिवोऽहम् ।। 4 ।। )

I have neither merit (virtue), nor demerit (vice). I do not commit sins or good deeds, nor have happiness or sorrow, pain or pleasure. I do not need mantras, holy places, scriptures (Vedas), rituals or sacrifices (yagnas). I am none of the triad of the observer or one who experiences, the process of observing or experiencing, or any object being observed or experienced. I am indeed, That eternal knowing and bliss, the auspicious (Shivam), bliss and pure consciousness.

____

Gloss: You can say you don’t need rhythm and ritual, but this would be a lie. You can say that you’ve overcome your magical thinking, but is there really no eight year-old trembling in your heart? Okay: Śiva deconstructs convention. At the end of deconstruction, what do we even want to reassemble? In the purāṇas the universe is described as expanding on Śiva’s inhale, and dissolving upon his exhale. In this verse, Śaṅkara tries to isolate the exhale from the inhale. But Śiva-as-chase must go farther, as the oscillation between things that build and order and things that melt and blend.

____

- na me mṛtyuśaṃkā na me jātibhedaḥ

- pitā naiva me naiva mātā na janmaḥ

- na bandhur na mitraṃ gurunaiva śişyaḥ

- cidānandarūpaḥ śivo’ham śivo’ham

(न मे मृत्युशंका न मे जातिभेदः, पिता नैव मे नैव माता न जन्मः । न बन्धुर्न मित्रं गुरूर्नैव शिष्यः, चिदानन्दरूपः शिवोऽहम् शिवोऽहम् ।। 5 ।। )

I do not have fear of death, as I do not have death. I have no separation from my true self, no doubt about my existence, nor have I discrimination on the basis of birth. I have no father or mother, nor did I have a birth. I am not the relative, nor the friend, nor the guru, nor the disciple. I am indeed, That eternal knowing and bliss, the auspicious (Shivam), bliss and pure consciousness.

____

Gloss: I often feel the benefit of transparent disconnection from cognition when I am overwhelmed. The autonomic nervous system rolls along, mostly unperturbed, beneath my anxieties. It can be socially stimulated, but it’s not socially identified. Śiva here may mean you can always rest in something beneath the busy matrix of connections. This rest is temporary. Perhaps no more than a few breaths, before your relationality reasserts itself. For those lacking privilege who haven’t the time to feel this, perhaps Śiva is the warrior that fights for this justice.

____

- ahaṃ nirvikalpo nirākāra rūpo

- vibhutvāca sarvatra sarveṃdriyāṇaṃ

- na cāsangata naiva muktir na meyaḥ

- cidānandarūpaḥ śivo’ham śivo’ham

(अहं निर्विकल्पो निराकार रूपो, विभुत्वाच सर्वत्र सर्वेन्द्रियाणाम् । न चासङत नैव मुक्तिर्न मेयः, चिदानन्दरूपः शिवोऽहम् शिवोऽहम् ।। 6 ।। )

I am all pervasive. I am without any attributes, and without any form. I have neither attachment to the world, nor to liberation (mukti). I have no wishes for anything because I am everything, everywhere, every time, always in equilibrium. I am indeed, That eternal knowing and bliss, the auspicious (Shivam), bliss and pure consciousness.

____

Gloss: This is the spring day. Sunlight streams through the crack in the blind beside my window seat. The wheels chirp their touchdown on the asphalt of Toronto. It could be anywhere, but this is Toronto. Or so they say. It should probably always be Toronto for me, as it’s unsustainable to be flying around like an asshole in a world so real it is burning. That’s something you never had to consider, dear Śaṅkara, now is it?

____

So many moments of infinitude, made meaningful by every way in which I’m bound.

____